Cloth face masks have become part of the daily routine for many of us. The first thing I did at the beginning of the pandemic last year was buy some cloth face masks for my mom, who is 68 years old and has delicate health. Nearly a year after that purchase, my mom is vaccinated, but she still wears her cloth face mask religiously every time she goes out in public. It’s her shield.

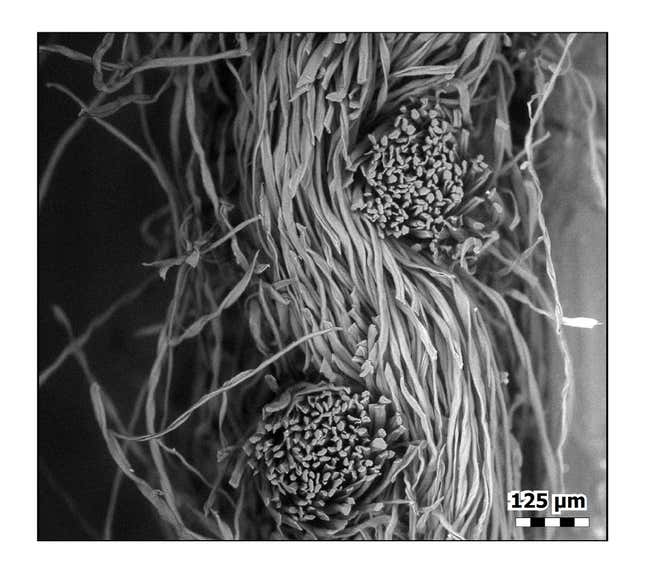

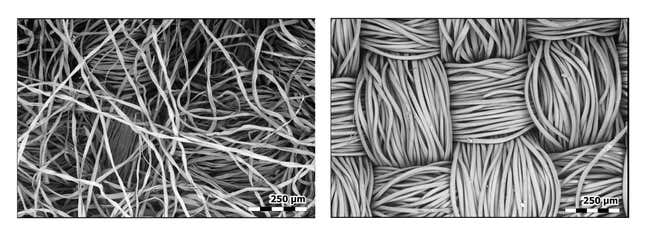

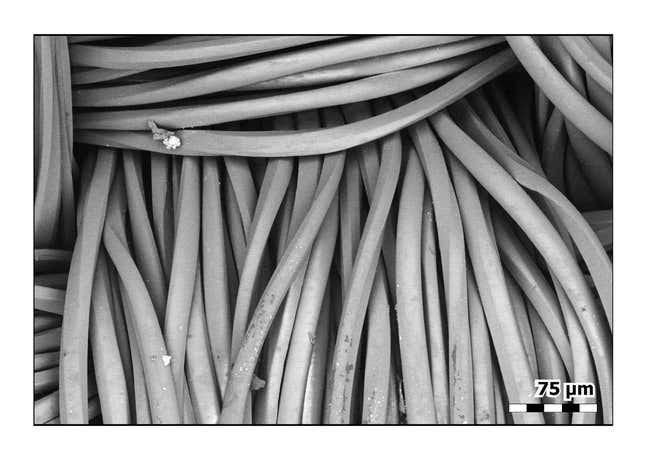

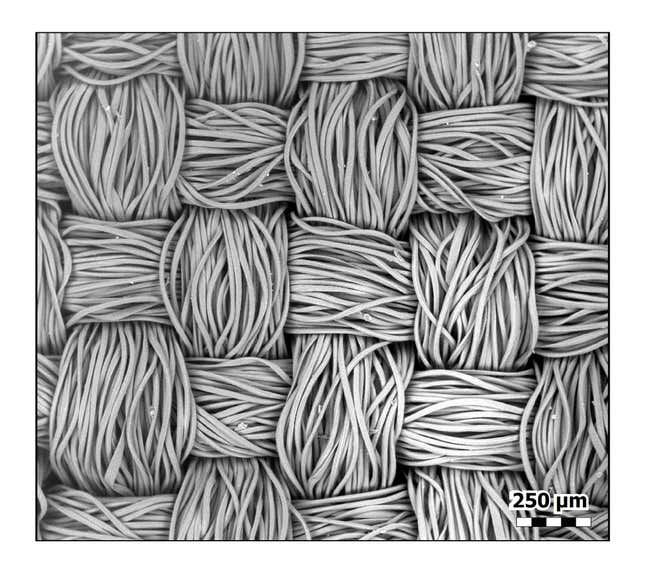

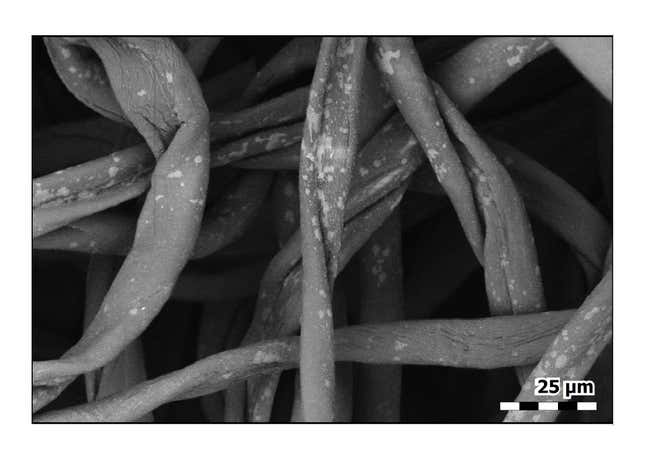

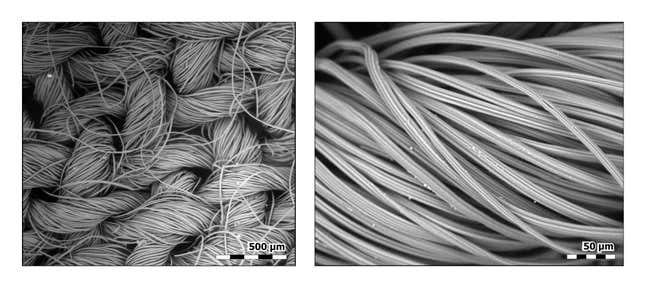

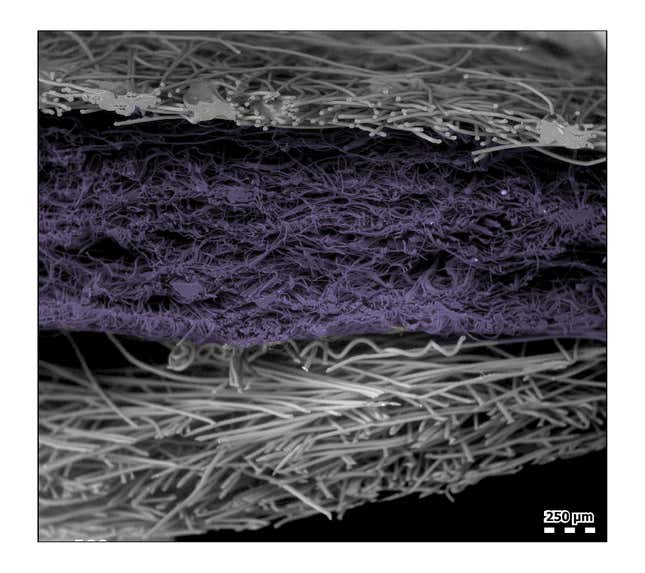

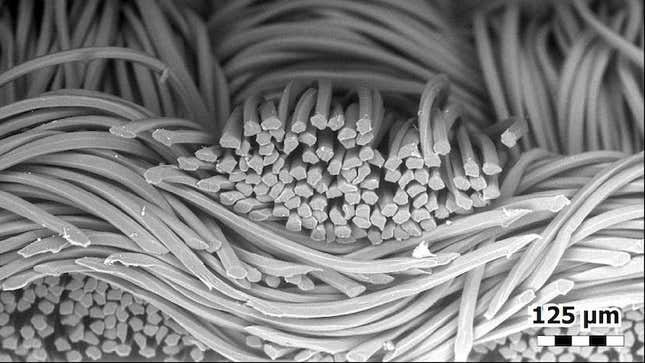

After seeing the destruction covid-19 has wreaked around the world, it can seem incredible that something as simple as a cloth face mask could slow the spread of the virus. (PSA: They do. Please wear a mask). However, you probably won’t feel the same way once you see the spectacular images of cloth face masks under a scanning electron microscope captured by researchers at the National Institute of Standards and Technology.