At first glance, Olivia Wilde’s elementary gaslighting thriller Don’t Worry Darling is the kind of sci-fi-adjacent movie that warrants a red hot spoiler alert before you read anything about it. That much has been clear since the film’s trailer dropped, introducing audiences to the idyllic, ’50s-style “Victory Project” and its subject, a very Stepford Wives Florence Pugh. Partying with bottomless cocktails in one scene and crushing an empty egg with utter shock in the next, the clip’s growing unease indicated that viewers should prepare for a ride full of secrets and twists.

Although this critic initially fell for the promise of its Pleasantville-meets-The Truman Show premise, that enthusiasm dimmed sharply upon discovering that the film’s feminist lessons are as simplistic as its obvious plot turns. Written by Katie Silverman, Carey Van Dyke and Shane Van Dyke, Don’t Worry Darling might have passed as mildly provocative in the ’90s, before Truman opened the escape door or Neo took the red pill. But Wilde’s film grafts these ideas to a pedestrian, you-go-girl template that sadly feels all too basic. If this counts as a spoiler, blame it on the marketing.

At least Wilde’s visuals are striking to look at. That aggressive ’50s aesthetic (as thematically on-the-nose as it may be), full of faux-vintage furniture pieces, a charming color palette of mustards and pistachio greens, precious television sets and more, is lavish, alarming in its symmetry and spotlessness, thanks to knowingly un-lived-in work from ace production designer Katie Byron. As cloudless mountains surround a cul-de-sac where a row of pristine old-school cars sit, Wilde and her team paint a picture so perfectly manicured that it’s anyone’s guess whether you’re in an affluent Los Angeles suburb or Pleasantville itself. Hastily, an excessive number of heavy-handed needle-drops—from “Comin’ Home Baby” to “The Oogum Boogum Song”—escort us into straight-couple-dominated Victory, where plucky homemaker Alice (a fearlessly terrific Pugh) lives with her husband Jack (Harry Styles, who is no match for Pugh).

Alice kisses her husband goodbye every morning, does chores around the house, slips into a pretty tea-length dress every evening, and sets out a beautiful dinner timed to his return. But who cares about supper, when you can have voracious sex on the table and smash all that pretty china just for kicks? Alice and Jack indulge themselves as much as they fancy without concern for the neighboring couples, who appear to live just as blissfully (and with as many orgasms). There’s Bunny, (Wilde, sporting Rita Hayworth’s sculpted, Old Hollywood waves), Peg (Kate Berlant), and Margaret (KiKi Layne), the latter of whom suffers from a series of mental health episodes. There’s also Violet (Sydney Chandler), a doe-like newcomer learning the ropes who gamely follows suit when the rest chant, “We’re changing the world!” at social gatherings.

Most of the men other than Jack are forgettable, a quality you sense is purposeful. The exception is the devilish, chilly Frank (Chris Pine), founder of the Victory settlement. All of the men work producing “progressive materials” for a happy future free of chaos for Frank at Victory’s secret headquarters, a location that’s out of bounds and supposedly dangerous for women. Curiously, Alice and her counterparts inquire only occasionally about their men’s work, instead, cooking, cleaning, and shopping extravagantly. “There is beauty in control,” Frank’s wife Shelley (a graceful Gemma Chan) lectures during the ballet lessons the rest dutifully attend.

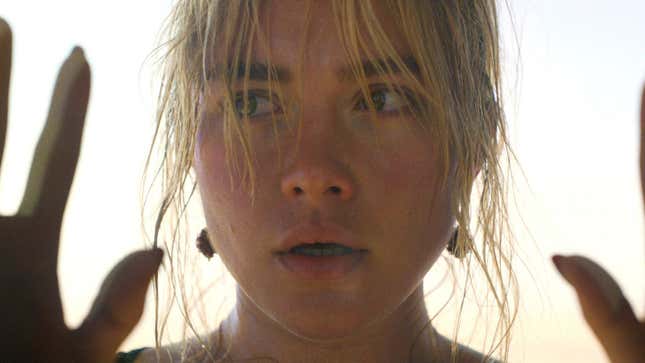

If only Wilde and the writers took Shelley’s advice to heart. Ironically, nothing seems controlled in Don’t Worry Darling, which obeys only inconsistent, “because I said so” rules that feel random: Why do the women sheepishly avoid The Headquarters—until they don’t? What’s outside Victory, and why don’t they ask that question? How long has Victory been there? It’s not until the disappearance of the increasingly rattled Margaret, whom no one takes seriously, that Alice grows skeptical. This is the great Florence Pugh, after all, and even the horrors of Midsommar couldn’t quell her curiosity. But even when she begins to uncover the truth, she becomes uncertain if Jack is trustworthy enough to be rescued if she can get them out of Victory.

Wilde, a capable director with an eye for movement and composition, enlists Darren Aronofsky’s cinematographer, Matthew Libatique, to create some petrifying, colorful visions—coupled with hypnotizing black-and-white burlesque dancing—that are pulled off with heady visual panache. After proving her knack for dynamic pacing on Booksmart, Wilde settles into an organic rhythm here, keeping viewers glued to the action. That’s why it’s an even bigger bummer when an alternate dimension of characters upends the tale, telegraphing an ending detectable from several Victories away.

Perhaps the chief deficit of Don’t Worry Darling isn’t even predictability, but a discernible lack of new ideas of its own. Patriarchy is bad and womanly autonomy is good? Who knew! But without spoiling too much, what’s especially curious is this film’s outdated and desperate approach to both motherhood and heterosexual sex, the latter of which looks phony and seems defined in male terms despite Wilde’s pronounced focus on female pleasure and feminism. Pugh, of course, is terrific, though she’s not just leading the film, she’s carrying it. But even if Don’t Worry Darling’s prettiness is intentionally engineered to make your skin crawl, all that sadly fills your brain when you turn away your gaze is a lingering emptiness—a film with no more weight than, well, a really good trailer.